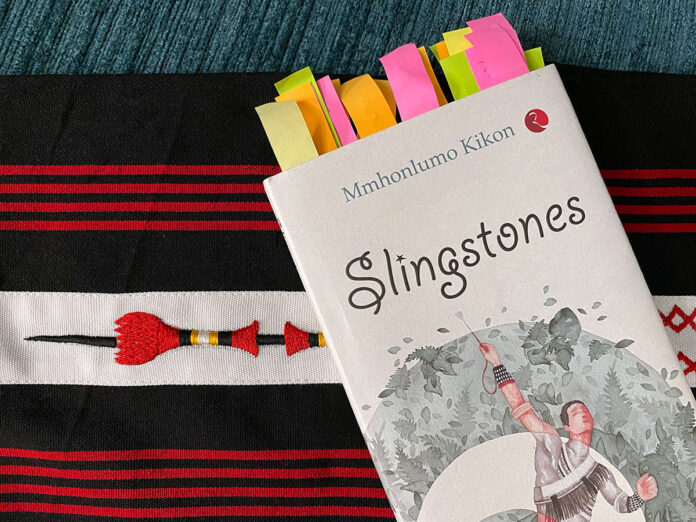

On its own, without context, Slingstones by Mmhonlumo Kikon is fascinating to read for its unique and unexpected narratives with a poetic twist of phrase.

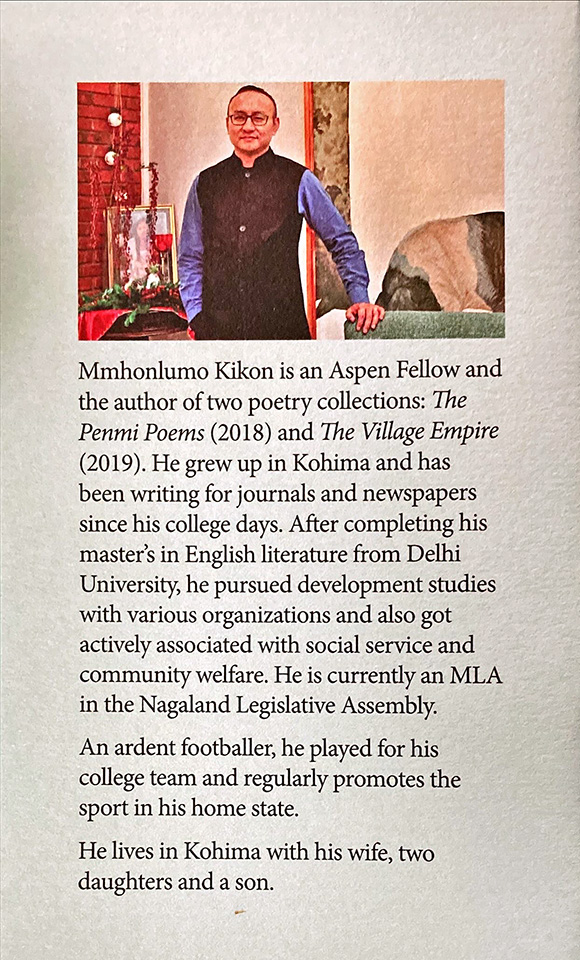

Then when you layer it with the context of the poet himself, and the context of Nagaland, the poetry slingshots to a level of brutal honesty, which is rare coming from a poet who is also a politician.

Mmhonlumo, or Mhon, the man I know, is one of the most well-read individuals I’ve met in my life. It is not surprising, therefore, that his thoughts are deep, and his poetry covers a wide range of subjects.

Slingstones is deep.

When I first read Slingstones, I liked it, but I didn’t love it.

Then I realized, unlike in Mmhonlumo’s “The Village Empire”, the poems in Slingstones are far more contexed and complex. So, to really appreciate Slingstones I read it again on a Sunday night when I was focused, and my mind was fully into it.

Then the width and depth of the poems hit me, and I was totally immersed in them.

Slingstones hits deep.

The poems take slingshots at everything and everyone that’s influenced life, the peace, and the potential of Nagaland. Like the British, American Christian Missionaries, Jawaharlal Nehru, and those leaders that serve their own interests under the pretence of Naga nationalism and identity. The underlying message is an awakening or a provocation to recognise, resist, and/or remove these elements.

Slingstones doesn’t shy away from calling out those that “raise an army of imbeciles and lead them to wilderness” or those that turned proud tribesmen into rickshaw pullers and “labour for Britain.”

It insightfully touches upon a wide range of subjects related to being a Naga and living in Nagaland.

Slingstones spread wide.

Grandma’s Curse references the dark history of Nagaland after India’s independence from the British, along with other poems that touch upon Naga nationalism, and the challenges of assimilation with mainland India.

Slingstones brings up racism, in Occupation, and Apes of the East.

Mmhonlumo writes about Self-Worth in the similarly titled poem, and about identity in Ethnographer.

Our Moon God reminds us that Nagas are originally Animists.

Farm Food, and The Middleman, reflect upon the good and the bad of farming in Nagaland.

Slingstones also turns to the dark Privilege of Suicide, the completely unexpected Engagement, and the little-known (and not spoken of) The Japanese Gene.

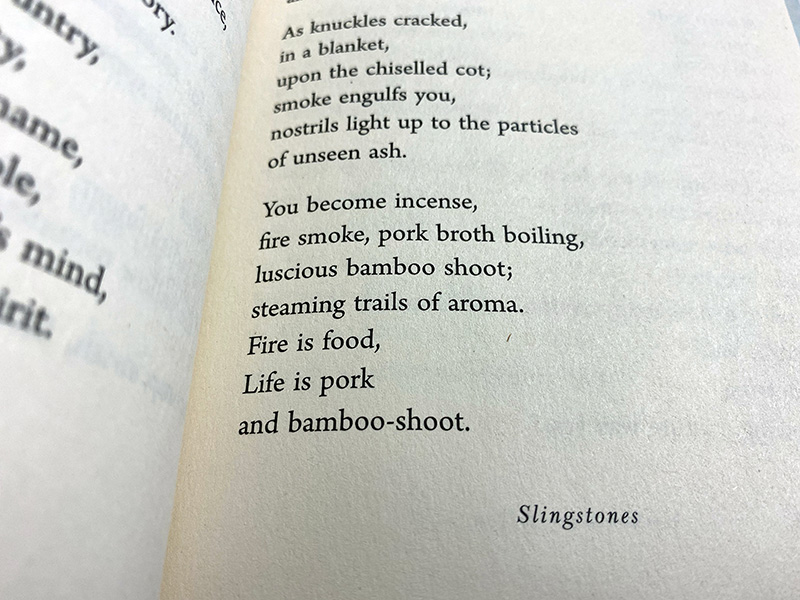

Then there is the beautiful By the Warmth of a Fireplace. It has my favourite line of the entire book, where Mmhonlumo romanticises “Fire is food, Life is pork and bamboo-shoot.”

In summary, Slingstones is a great read. And every time you read it, you will probably discover more layers behind the words that make up each poem.

This is not surprising, because the poet has a long road ahead to walk. As do his people. Fighting demons, both within and without. Clearly, as one of his Slingstones says, “he persists in the rustic sanity, in the urban mad, in the crazy, blood-baying, head-hunting, gory glory chorus of a proud people”

Great articles. Enjoyed reading them.

In the Article on “Nagaland. Not Just Hornbill”, please check the picture featured for Naga King Chilly. (Commenting here because comments were closed in that Article)

Thank you for your kind words. I am happy you enjoyed reading my articles.

I have reopened comments on every post/article. I must have turned off the commenting feature by mistake. Thanks for pointing that out too!

Please elaborate on the part about the Naga King Chilly picture. Is it not correct?